For much of the 20th century, being transgender in the United States wasn’t just socially unacceptable—it was treated as a crime. Not necessarily by name, not always with laws that explicitly said “trans people are illegal,” but in practice, that’s exactly how it worked. If you dared to live as your true self, you could be arrested, institutionalized, surveilled, denied work, or kicked out of public spaces.

This wasn’t a side effect of the system. It was the system. It was the law. And the criminalization of trans lives was woven into daily life in countless ways—some blunt and brutal, others more bureaucratic and insidious.

So, how exactly was being transgender made illegal?

Let’s look at some of the tools used to enforce a strict, binary view of gender and punish anyone who stepped outside its rigid lines.

Table of Contents

Cross-Dressing Laws and the Policing of Appearance

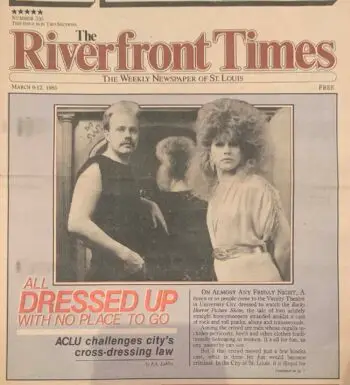

One of the most obvious ways trans people were criminalized was through laws against so-called “cross-dressing.” These laws cropped up in cities and towns across the United States starting in the mid-19th century and continuing well into the 20th century. They were often vague, banning people from wearing “clothing not belonging to their sex” or otherwise presenting in a way deemed inappropriate by local authorities.

This wasn’t about preventing disguise or fraud. It was about enforcing strict binary gender roles and punishing those who violated them. Police used these laws to harass, arrest, and publicly shame trans and gender non-conforming people. A person perceived as wearing “the wrong clothes” could be detained, fined, or worse. Even when these laws weren’t formally on the books, police found workarounds.

One infamous example is the so-called “three-article rule,” a loose guideline claiming individuals had to wear at least three articles of clothing that matched the gender they were assigned at birth. The rule wasn’t enshrined in law, but it was often cited during arrests and used as a way to justify discriminatory policing.

Bars and nightclubs that served trans patrons were frequently targeted. During raids, police would line people up and inspect their clothing. What they were really doing was deciding who was “male enough” or “female enough” to be out in public. If you didn’t pass that test, you could find yourself in a jail cell.

This constant threat of arrest had chilling effects. People had to think carefully about what they wore, where they went, and who they might run into. Something as simple as going to a bar or taking a walk at night could turn dangerous fast.

Medicalization and Involuntary Institutionalization

While law enforcement targeted trans people in public, the medical system played its own role in making trans lives unlivable.

For much of the 20th century, being transgender was officially classified as a mental illness. Doctors and psychiatrists labeled trans identity as “gender identity disorder” or even as a form of psychosis. This meant that people who identified as trans could be institutionalized against their will, denied medical care, or forced to undergo humiliating evaluations.

Even those seeking help were often punished. Trans people who turned to the medical system looking for support, understanding, or access to transition-related care were instead met with gatekeeping, suspicion, and control. Before hormone therapy or surgery was even an option, trans people had to “prove” they were serious, often by living full-time in their affirmed gender for years without support, facing intense scrutiny and often ridicule.

The process was dehumanizing. It stripped people of autonomy and framed their identities as something to be fixed or cured.

And for those who didn’t conform to these narrow expectations—who weren’t “passable,” who didn’t want surgery, who were poor, disabled, or didn’t fit the white, middle-class mold of the “ideal patient”—care was often completely inaccessible.

Surveillance, Policing, and the Criminalization of Daily Life

Trans people weren’t just arrested for the clothing they wore. They were surveilled and criminalized in countless other ways. Police departments actively monitored queer and trans communities, kept lists of suspected LGBTQ+ individuals, and used entrapment tactics to make arrests.

Public bathrooms, parks, bars, and even sidewalks became dangerous places. Merely existing in these spaces as a trans person could make you a target.

In many cases, trans women—especially trans women of color—were automatically profiled as sex workers. Police would arrest them under vague loitering or prostitution laws, regardless of what they were actually doing. The assumption was that a trans woman must be doing something illicit, simply because she was trans.

These arrests weren’t just about removing people from public view. They often came with violence, verbal abuse, and public shaming. And they left lasting scars: a criminal record could mean losing your job, your housing, or custody of your children.

The message was clear: trans people didn’t belong in public life.

ID Documents, Bureaucracy, and Legal Erasure

Another major tool of trans criminalization came not from police or doctors, but from paperwork.

As society became more reliant on identification documents—driver’s licenses, Social Security cards, birth certificates, school and employment records—it became harder and harder for trans people to navigate their daily lives.

Your ID needed to match your appearance. Your records needed to be consistent. And if they weren’t, you could be denied access to work, housing, healthcare, or even the right to vote.

For many trans people, changing these documents was either legally impossible or came with unreasonable requirements, like proof of surgery, court orders, or notarized letters from medical professionals.

That meant every time you applied for a job, cashed a check, or interacted with a government agency, you risked being outed. You risked harassment. You risked violence.

In a world that runs on paperwork, trans people were systemically erased—and then punished for not existing.

Fighting Back

Despite all of this, trans people refused to disappear.

They built underground networks and mutual support systems. They fought for legal recognition, safer spaces, and medical access. They pushed back against police harassment and demanded to be seen and respected.

And over time, they began to change the world.

None of the rights and recognition trans people have today happened by accident. They were hard-won by people who faced down impossible odds.

That’s why it’s so important to remember this history. To remember that the fight for trans rights isn’t just about pronouns or bathrooms—it’s about survival. It’s about dignity. It’s about undoing the legal, medical, and cultural systems that once made our existence a crime.

And in many ways, that work isn’t over. Trans people are still being policed, still being denied care, still facing daily threats to their safety.

So let’s keep telling these stories. Let’s keep shining a light on the past, so we can better understand the present, and fight for a future where no one is criminalized just for being who they are.