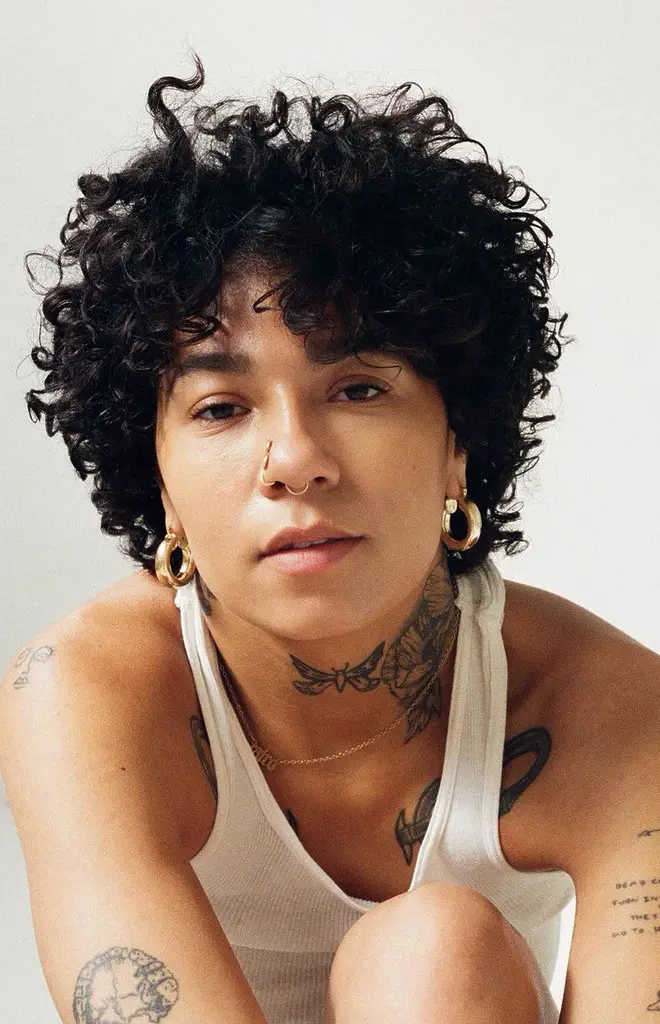

By: Cairo Levias (they/them)

Maybe it’s supposed to be messy

My story started early. Maybe around age 10 or 11. Up until this point in my life I’d been othered in more ways than how I thought about gender. I had grown up as the only black kid in an all white school and that was enough to make me feel alone. But I have this memory, one of the clearest from that time.

I was at the top of the stairs on my way down to the kitchen when I looked at the TV, and something in me just told me to stop right where I was. On the TV, I saw what looked like a woman, but also a man. Her chest was bound with what looked like a bandage, and she was kissing another woman. I’d never seen anything like that in my life. I remember shouting to my mom who was sitting on the couch below. Something in her demeanor looked like she felt startled. Almost caught.

She immediately flipped the channel and greeted me back. What about that image did she not want me to see? The feelings that rushed in when I saw that clip felt like what I now would describe as a reflection, a mirror. I felt seen and at the time I had no explanation or idea as to why. I later learned the movie was called Boys Don’t Cry.

As I grew into what I could barely recognize as my body, I dissociated from the little nets in my brain that felt wrong in my body and in this world. I grew up to move to a place with more people that looked like me—not a lot, but some. I struggled with some trauma and habits throughout my journey.

I can’t say the lead-up to my eating disorder or drug addiction had nothing to do with gender, because it absolutely did and was but a piece of my seemingly broken identity. Feeling trapped in a mind and body that felt foreign, finding things I could control was the goal. That being said, my discomfort transferred into eating habits and substances. These were things I could control, or so I thought.

As I transferred to an art high school, I was still pretty confused and felt contorted into the idea of what a girl is. Deep inside, I knew something had to change because I knew other people didn’t feel like this. I stepped into my new school and looked around. There were people defying gender rules left and right. I learned a lot through my peers about gender and sexuality. Before this point, I knew I definitely had attraction to female-bodied individuals and male-bodied individuals at the same time. I’d try to talk to my mom about it and all she had to say was that I need to “pick one.” As if I wasn’t confused enough about who I was, she was telling me there’s only one way to be. I already was still one of eleven black students at this art school, so again, I felt alone in a new way. I didn’t know how to be a girl, or boy, or Black enough or white enough.

I didn’t know how to be.

Fast forward. I can’t remember when I first discovered the idea of a nonbinary identity, my memory hasn’t sharpened in the interim due to the drugs and not taking care of my mind. But I do remember the feeling, clear as day. It’s as if every singer on planet earth had broken the walls of my chest with the sigh of finally feeling reflected in a way no one had ever reflected me before. And it felt like a safe, cozy blanket of a term. Although I didn’t entirely know what that meant in the grand scheme of things, something in that term felt absolutely right. It checked all of my freedom boxes: mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. A resounding yes rang throughout my body as deep as bone marrow.

After some trial and error and ups and downs, I tried talking to my parents again—saying and insisting that I’m not a girl, but I’m not a boy either. I told them I’m nonbinary. Again, my mother told me to pick one. My dad on the other hand didn’t really have judgements. He just thought that whatever made me happy he would agree with. This gave me the courage to keep exploring.

As I continued the exploration of gender both physically and mentally—and of course how it affected my sexual identity—I tried whatever I could. First things first, I shaved my head. This wasn’t all due to the gender shifts that were happening, but also due to the fact of having a white mom who insisted I straighten my hair to look “prettier.” That in itself was enough to disconnect me from myself, so I protested that and decided there was no need for hair at all and no need to live up to her standard of “pretty,” at least in that way.

I still struggled with body image and body dysmorphia due to my off and on disordered eating. But at the very least, I made changes that felt freeing. I tried new clothes, new makeup, and everything I could think of to feel more at home in my body. I remember some of my favorite things to wear were my dad’s summer silk button-downs. They were flowy and drapey and made me feel strong and tough—masculine in a way that wasn’t jarring.

A masculine appearance for one period of development felt good for me. A big part of wanting to be more masculine was to avert the eyes of men that had been following me since a young age—men that took me away from my life and exploited me for a period of time. (That story is much darker, and for another time.) My masculine exploration lasted all throughout high school. Once I graduated and moved out on my own, I faced a lot of hardships that no 17-year-old should have to endure, but here I am alive, and writing this for you.

Let’s skip to the good part, though. In May of 2017, I was about to turn 19, and had been through the wringer of existence the last couple of years. That year, I finally got clean. The first of May and most of that year is blurry due to the detoxing and trying to rewire the world around me.

At 18 months clean, I made a big jump and moved from the West Coast to NYC. Boy, was I in for a wild ride with gender. It was messy, but I wouldn’t change it for the world. I was living with my little sister and a couple friends in a big beautiful loft in Brooklyn. I started making friends in the sober community with people of all sorts of identities. It felt like I was a lucky child on Christmas morning. Like an entire world had opened up before my eyes and I could finally see clearly. Gender itself pounded through my head and straight out my ears like a hurricane and any rules I thought there were finally crumbled in my hands. I could finally stop explaining myself, my gender, my Blackness, all of it. I could just learn how to be.

When I think back on that period of time, I can see that I was one of the most present versions of myself that I could possibly be when it came to gender. As my definitions faded and new love emerged from dark alleyways and basements with fold-out chairs, I grew into the person I could finally say looks and feels how I was supposed to. It’s hard to put that feeling into words, now that I’m trying to.

Throughout this time in NYC, I saw myself reflected in the fluidity of the city itself. I could wake up in different dimensions of gender everyday and was free to reflect that however I wanted to—physically, spiritually, emotionally. It’s as if the last puzzle piece finally slipped in when I wasn’t looking.

In a series of events that led me to move back home, I kept every ounce of inspiration I got from my time in New York and took it with me. Since then, I’ve had a lot of mountains to climb in terms of identity. But in the end, well. Maybe this isn’t the end.

I’ve been a riverflow of new selves and new reasons to be myself. I’ve been a trans boy, I’ve been a woman, I’ve been neither, and I’ve been everything at once. I wouldn’t have it any other way. That little angel sneaking a peek at a transgender boy on the TV behind their mom finally knows why they felt so reflected and confused all at the same time. That little beautiful baby no longer has to be “pretty,” “poised,” “charming,” or a “good girl” again. That same beauty gets to present not only how they feel in their body through clothes and personal appearance, through writing and relationships, and by learning to take everything one day at a time.

Today, I get to wake up and be reflected in my spirituality, relationships with myself and my chosen family, and through the eyes of the younger me—who has no idea what any of this means. I write this to tell them and to tell you that it’ll be messy. It’ll be feral at times. But no one in this world gets to be you the way that you do. Gender is a social construct for the patriarchal white-centered agenda and unsubscribing from that does not make you any less beautiful and capable of your dreams whatever they may be.

Cairo Levias (they/them) is a model, stylist, muse, and mystic. From walking the runways of New York Fashion Week to designing seasonal narratives for fashion brands, Cairo’s expansive vision extends beyond gender to life’s possibilities. They live with their husband and two perfect kitties.

As the largest provider of gender-affirming care for the trans and nonbinary community, Plume is committed to providing information about many types of information, including questions about hormones like estrogen and testosterone, gender transitioning tips and experiences, and guidance on social transition and self care.

While we strive to include a diverse range of voices and expertise, not everything will be for every person. Each individual’s experience is unique, and the information Plume provides is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Always first seek the advice of your primary and/or specialist physician, the Plume Care Team, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition, your mental health and emotional needs, or your health care needs regarding gender-affirming hormone therapy. If you are experiencing an emergency, including a mental health crisis, call 911 or reach out to Trans LifeLine.